This post is not a How I found an RCE.

It’s How I didn’t find one - and what the journey taught me.

This is a walk-through of my attempt to analyze the Nokia G2425G router, bypass client-side filters, explore CGI binaries, and understand how the backend validates inputs.

The router fought back harder than expected.

Most SOHO routers expose diagnostic tools like:

- Ping

- Traceroute

They are often backed by shell wrappers like ping, traceroute, sh, or BusyBox utilities. Historically, input validation on these endpoints has been terrible, leading straight to command injection.

On the Nokia G2425G:

The UI provides fields to enter IPv4, IPv6, or domain names.But the client-side JavaScript aggressively validates every input:

- Regex for IP or hostname

- Stripping unsafe characters

Rejecting anything outside the expected pattern

At first, it felt like jail.

Breaking the Client-Side

If JavaScript blocks you, rewrite it.

I opened the browser’s DevTools → Sources → Workspaces and overrode the minified all.min.js file.

Inside this file was the validation logic for the ping/traceroute input:

function isValidIpAddress(e) {

if (ipParts = e.split("/"),

2 < ipParts.length)

return !1;

if (2 == ipParts.length && (num = parseInt(ipParts[1]),

num <= 0 || 32 < num))

return !1;

if ("0.0.0.0" == ipParts[0] || "255.255.255.255" == ipParts[0])

return !1;

if (addrParts = ipParts[0].split("."),

4 != addrParts.length)

return !1;

if ("0" == addrParts[0])

return !1;

for (a = 0; a < 4; a++) {

if (!/^[0-9]*$/.test(addrParts[a]))

return !1;

if (isNaN(addrParts[a]) || "" == addrParts[a])

return !1;

if (num = parseInt(addrParts[a]),

isNaN(num) || /\s/.test(addrParts[a]))

return !1;

if (num < 0 || 255 < num)

return !1

}

var t = parseInt(addrParts[0])

, n = parseInt(addrParts[1])

, r = parseInt(addrParts[2])

, e = parseInt(addrParts[3]);

if (1 <= t && t <= 223 && !ipParts[1]) {

if (127 == t)

return !1;

if (255 == e || 0 == e)

return !1

}

if (1 <= t && t <= 127) {

if (127 == t)

return !1;

if (255 == n && 255 == r && 255 == e || 0 == n && 0 == r && 0 == e)

return !1

} else if (128 <= t && t <= 191) {

if (255 == r && 255 == e || 0 == r && 0 == e)

return !1

} else {

if (!(192 <= t && t <= 223))

return !1;

if (255 == e || 0 == e)

return !1

}

if (2 == ipParts.length) {

for (var i = 32 - parseInt(ipParts[1]), r = t << 24 | n << 16 | r << 8 | e, o = 1, a = 0; a < i; a++)

o *= 2;

e = (r & --o).toString(2),

r = o.toString(2);

if ("0" == e)

return !1;

if (e.length == r.length && e.indexOf("01") < 0 && e.indexOf("10") < 0)

return !1

}

return !0

}

By overriding the JavaScript in a local DevTools workspace, I disabled the client-side validation entirely. With those checks gone, the UI started accepting every kind of input I threw at it.

;ls

$(whoami)

| cat /etc/passwd

Great, right? Nope.

The router responded with: ❌ Unsafe characters detected

This meant one thing: ✔ There is a server-side validation layer.

And now the real investigation begins.

Without UART, How Do I Analyze the Backend?

Two options:

Dump firmware via UART / SPI flash reader.

Search online for the exact firmware version.

I didn’t have any hardware tools at that moment, so I went with Option 2.

And surprisingly, it worked - I got the firmware online.

Firmware Tear-Down With Binwalk

After downloading the .bin file:

binwalk -e firmware.bin

Exploring the Filesystem

The webs/ directory contained:

HTML & JS

CGI endpoints

I checked /etc/shadow hoping to brute-force root:

root:$1$xxxxxxx$xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx:...

But cracking attempts failed.So password cracking was a dead end… time to reverse engineer.

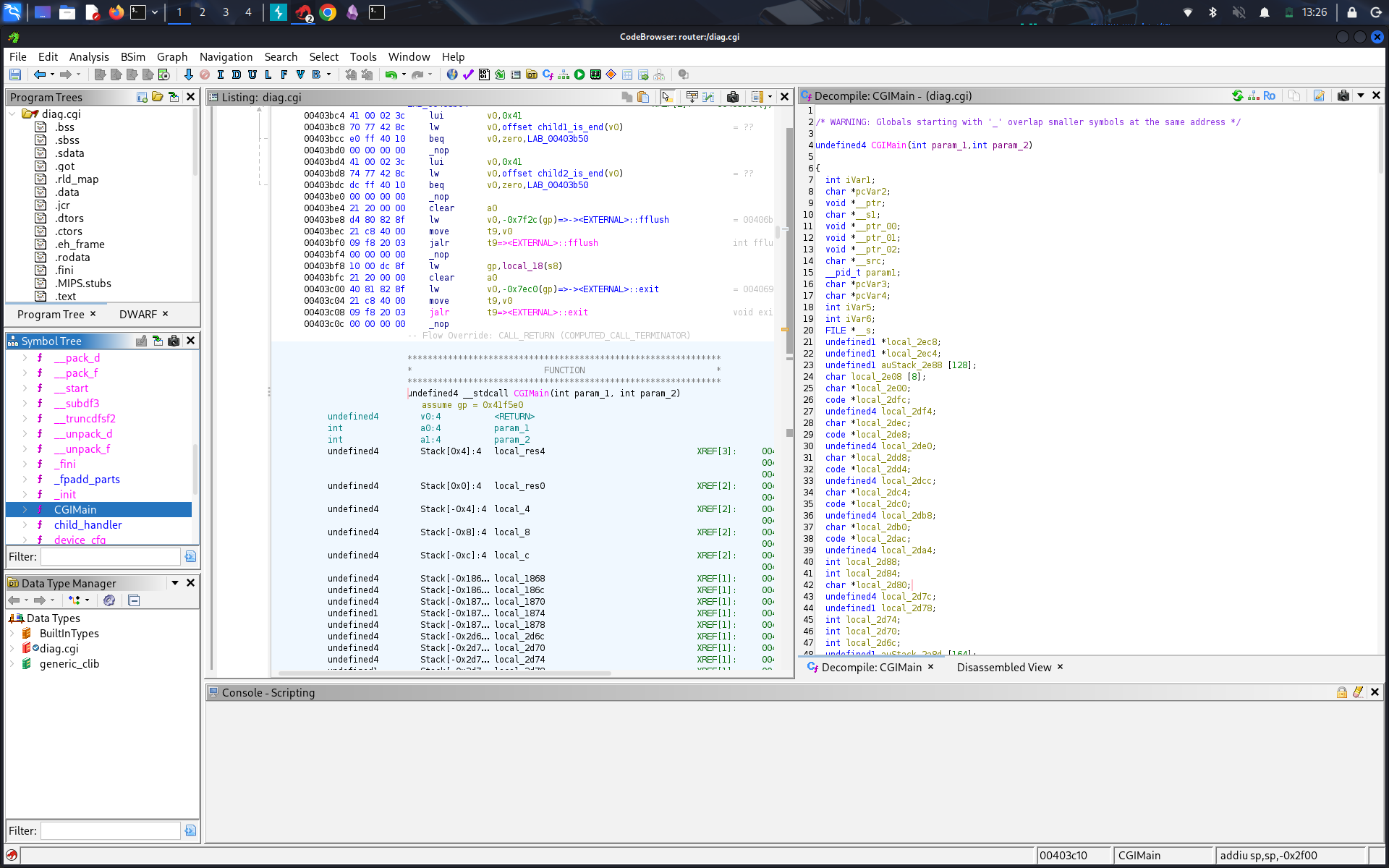

Feeding the CGI Binaries to Ghidra

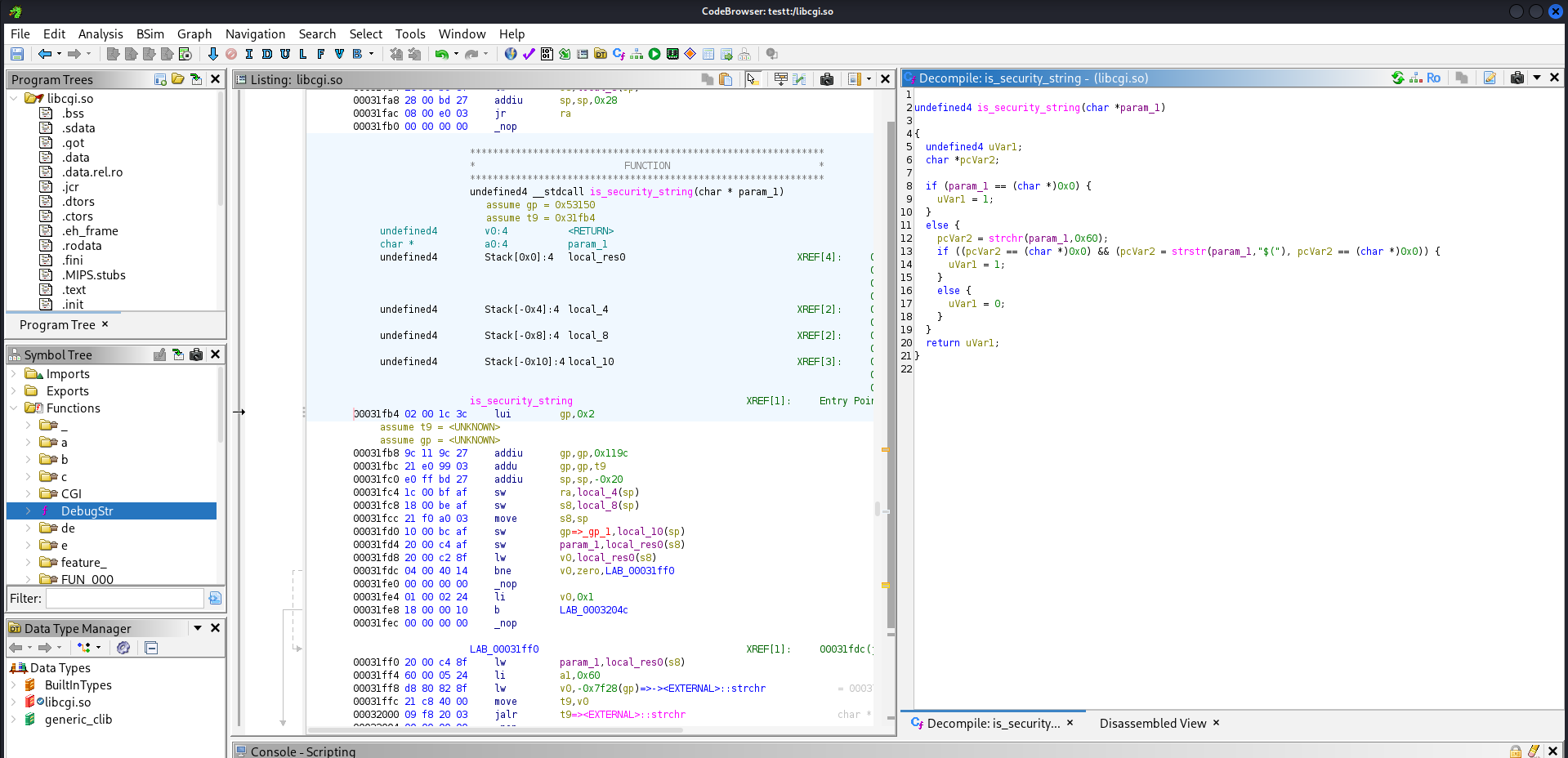

When I loaded diag.cgi into Ghidra, one function immediately caught my eye: is_security_string().

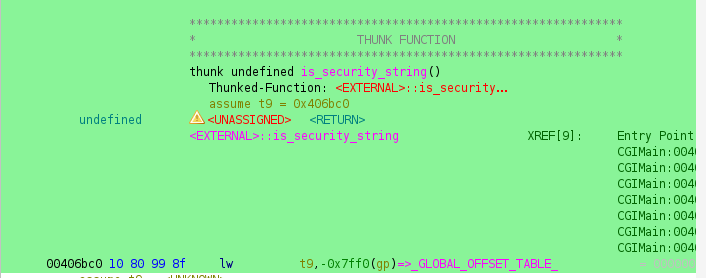

Jumping into the function, Ghidra marked it as a thunked function, which meant it wasn’t defined inside the CGI binary itself but was being resolved from a shared library.

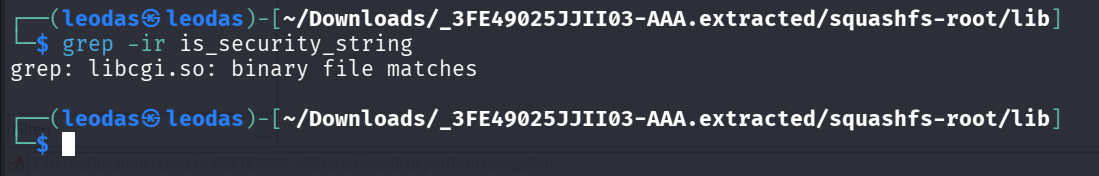

So I headed into the lib/ directory inside the extracted firmware and started grepping through the binaries for any reference to that function or its string patterns.

That search led me to libcgi.so, where the actual validation logic lived.

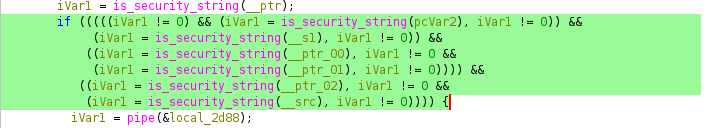

Inside this library, I found a tight allow-list check—specifically filtering out characters like ` and $ to prevent classic command injection vectors.

At first glance, it looked like the usual sanitization layer, but I wanted to understand how the command was actually executed. Sanitization alone doesn’t tell the full story.

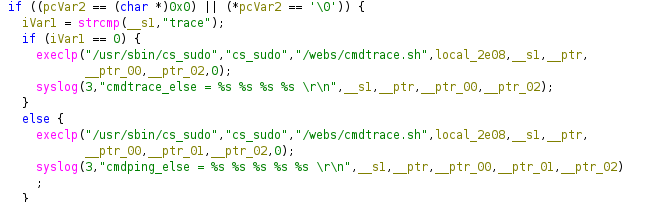

Digging deeper into the decompiled flow, I saw that diag.cgi didn’t directly run system commands. Instead, it forwarded the sanitized user input to a shell script named cmdtrace.sh.

Once I opened that script, the final puzzle piece clicked: every user supplied value was passed as an argument, wrapped inside a fixed command structure:

ping6 $ip -s $timeout

At first, it looked like typical Bash argument handling, but the real defense mechanism wasn’t inside the script at all. The actual command execution happened through the C function execlp(), invoked from inside the CGI binary.

And this changes everything.

Why execlp() Matters

Unlike system() or backtick execution, which invoke a subshell and allow string interpretation, execlp() does not involve a shell at all.

So even if user input survived the client-side bypass and slipped past the library sanitization layer, the execution path itself was designed to resist injection. Anything passed to execlp() is treated strictly as an argument, not as part of a shell command.

No RCE this time - just a router that fought back with real defenses. But every failed payload taught me where the cracks could be next time.

Credit to @jopraveen for being part of the exploit chase.